2022 MET Gala anticipation

At the bottom of the Met Gala invitations sent every spring is an inscription small in size but vital in importance: the dress code. In 2020, for “Camp: Notes on Fashion,” it was studied triviality. In 2021, for “In America: A Lexicon of Fashion,” it was American independence. And come May 2, 2022, for “In America: An Anthology of Fashion,” it will be gilded glamour, white-tie.

Oh, yes. Dust off Edith Wharton’s Age of Innocence and The House of Mirth. The 2022 Met Gala will ask its attendees to embody the grandeur—and perhaps the dichotomy—of Gilded Age New York. The period, which stretched from 1870 to 1890 (Mark Twain is credited with coining the term in 1873), was one of unprecedented prosperity, cultural change, and industrialization, when both skyscrapers and fortunes seemingly arose overnight. Mrs. Astor and her 400 ruled polite society until the new-money Vanderbilts forced themselves in. Thomas Edison’s light bulb, patented in 1882, alit first The New York Times building and then the entire city. Alexander Graham Bell’s 1876 telephone made communication instant—and created a demand for operators to man the lines, leading one of the first mass waves of women into the workplace. Wages skyrocketed past those in Europe (although, as Jacob Riis

Colors were rich and deep jewel tones. Lighter colors were only worn only at home, as they were impractical while walking in the streets of New York. Hats were a necessity when going out and often were adorned with feathers. (In fact, the Audubon Society was founded in 1895 in response to protecting birds from the millinery trade.) Corsets were commonplace, and in the 1870s to late 1880s, women embraced bustles to elongate their backsides—in fact, a commonly repeated conceit was that a bustle should be big enough to host an entire tea service. By the 1890s, however, they faded out of fashion, replaced by mutton sleeves, bell-shaped skirts, and pompadour hairstyles. This aesthetic was only further popularized by illustrator Charles Dana Gibson, whose pen-and-ink illustrations

That’s not to say that all Gilded Age fashion was formal. As leisure activities like bicycling and tennis became popular among the well-heeled set, sportswear, for the first time, became an integral part of one’s wardrobe. Many women adopted a shirtwaist ensemble—or a long skirt paired with a feminine blouse—which allowed for easier movement, as perhaps best exemplified by John Singer Sargent’s 1897 portrait of Gilded Age socialite Edith Minturn.

However parties, balls, and soirées brought out the most extravagant style this country has ever seen. The opera, which was often frequented by the upper echelon, had a strict dress code: Women put on tulle dresses exposing their legs.

Outrageous costume parties thrown by the most talented hostesses of the day had frenzied and fantastical fashions. Take Alva K. Vanderbilt’s March 1883 event for her daughter, Consuelo, which became known as the most lavish celebration of the era. “The Vanderbilt ball has agitated New York society more than any social event that has occurred here in many years,” The New York Times wrote dramatically at the time. “Since the announcement that it would take place, which was made about a week before the beginning of Lent, scarcely anything else has been talked about.” Guests spent outlandish attention to detail—and amounts of money—on their outfits: Alice Claypoole Vanderbilt came dressed as an electric light bulb, which meant a white gown satin trimmed with diamonds,

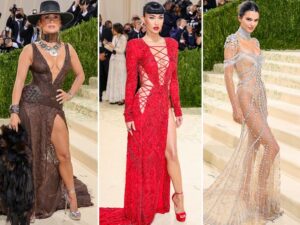

Time will only tell how the guests interpret the dress code for the 2022 Met Gala when they arrive to the storied museum on the first Monday in May.

Culled from

Vogue